SADDLE STITCH

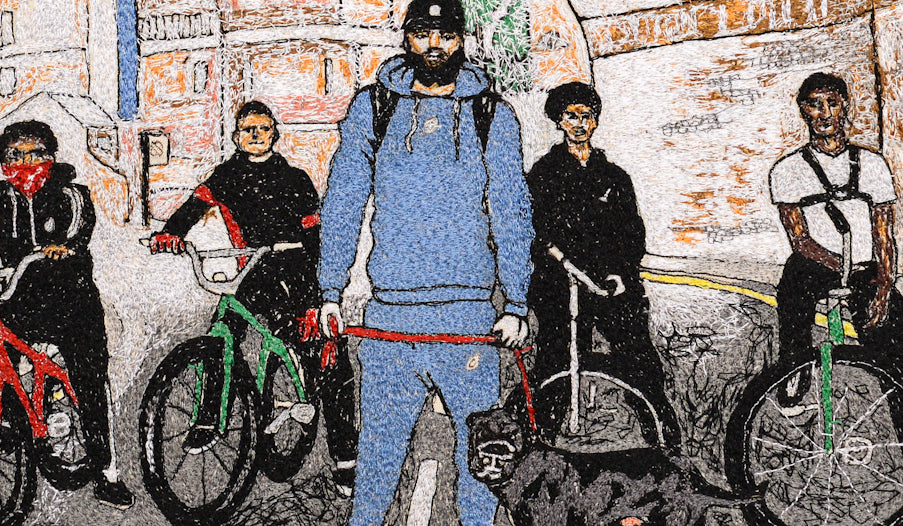

Image: Detail of Community. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

James Fox is a Lancashire-based textile artist working in machine embroidery and reverse appliqué. His exhibition, Freedom of Movement, is at The Knitting & Stitching Show at Harrogate Convention Centre from 17-20 November, 2022. For SELVEDGE, he talks to Julie Parmenter.

JULIE PARMENTER: James, your Harrogate exhibition is a celebration of freedom of movement and includes a homage to the humble bicycle. Can you tell us why bikes were so inspiring to you, in this particular body of work?

JAMES FOX: The invention of the ‘safety bicycle’ in the 1880s, as well as the development of the railway system, allowed movement around the country as never before. The working class were able to get out from the grime of the factories, and cycle into the countryside on their day off. The owners of the factories they worked in could travel by train to their recently acquired shooting estates for the weekend. At the same time, socialism was spreading across Europe. These two factors inevitably conjoined, and socialist cycling clubs sprang into existence all over the U.K.

Image: We Have Nothing To Lose But Our Chains. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

Image: We Have Nothing To Lose But Our Chains. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

The safety bike also contributed to the women’s rights movement. To quote Susan B. Anthony, “the bicycle has done more to emancipate women than any one thing in the world.” She would go on to write: “I rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a bike. It gives her a feeling of self-reliance and independence the moment she takes her seat; and away she goes, the picture of untrammelled womanhood.”

Image: The Impact of Cycling. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

Image: The Impact of Cycling. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

Using these historical factors, I began a series of works which also involved contemporary subjects— alternative transport policies, climate change, social reforms and working-class concerns. I found further inspiration in ‘Bikestormz’, a recent phenomenon in bicycle culture, where inner city youth take to the streets on their bikes, pulling wheelies in shows of defiance and solidarity against knife crime and violence. Another cycling issue that caught my interest was the plight of zero-hours contract cycle couriers, who were striking for fair wages and working conditions.

Image: Revolutionary Wheels. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

Image: Revolutionary Wheels. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

JP: Trades Union banners have also influenced your work, and your exhibition features a Right to Roam banner. Can you tell us how you’ve drawn on these historic stitched protest works in your art?

JF: Trades Union banners have been a source of fascination to me for years. They represent and celebrate communities, unions, and organisations, highlighting unity, compassion, and strength— with the added bonus of craftsmanship, design, and pride. My works, NOT NOW TORY BOY and Right to Roam, nod to the tradition of banner making and comment on contemporary themes. Pithy headlines from the press dilute serious contemporary political and social issues, as well as celebrating historically important occasions.

Image: Detail of work. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

Image: Detail of work. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

JP: You have long been an observer of social, political, and economic change, and social commentary is an integral part of your work, woven into your designs. Is there something unique about textiles and stitching that lends them to the language of protest?

JF: Textiles, although often derided for their association with domesticity, are an important vehicle for commenting on, and sometimes criticizing, society, I believe. Textile art and its part in protest and political activism can be seen throughout history— from the Bayeux Tapestry to Union banners, AIDS quilts, and the more recent interest in craftivism. Using art, in particular textile art— even more specifically, embroidery —can be a valid and important means of responding to cultural, social, and political situations.

Image: Where there's a wheel. James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

JP: You have an art residency with Lancaster and District Homeless Action Service, where you have been working with clients to create embroidered stitched portraits. A touring exhibition has been promoting action to support the homeless. What has this experience meant for you personally, and for your art practice?

JF: I had been volunteering at LDHAS for a number of years, as well as being artist-in-residence for two. I’ve delivered art workshops, as well as producing art works which were then gifted to local schools, hospitals, and public buildings. During this time, I built up a relationship with some of the clients and decided to do some work around the theme of homelessness. I suggested drawing a series of their hands, which I found fascinating; they suggested I draw their faces. At first, I thought this would be intrusive, perhaps taking advantage of their situation. But homelessness can make you feel unwanted and invisible so, for some, to have someone spend time invested in you as a person can be a positive thing, in a life filled with negativity.

Image: James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

Image: James Fox. Courtesy of the artist.

In the 2020 pandemic, the homeless service closed due to Covid (it reopened in 2021). The government implemented a scheme to get rough sleepers off the streets (‘Everyone in’), which was mainly due to the perseverance of Baroness Louise Casey. Unfortunately, this was short-lived and, according to the homeless charity Crisis:

‘It is predicted that the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic risks a substantial rise in core homelessness, with overall levels expected to sit one-third higher than 2019 levels, on current trends. Levels of rough sleeping are also predicted to rise, despite the Government’s target of ending this form of homelessness by 2024.’

The experience of working with this group of people opened my eyes to a system that is almost impossible to navigate. It also politicised my practice, spurring me to start a PhD at Lancaster University.

Image: Right to Roam, behind MP Caroline Lucas. Photo: Phil White. Courtesy of James Fox.

Image: Right to Roam, behind MP Caroline Lucas. Photo: Phil White. Courtesy of James Fox.

JP: An exciting feature of your work for The Knitting & Stitching Show is sound, with two soundscapes accompanying your exhibition. What do you hope visitors will take from this fascinating sensory combination of spoken word and textile art?

JF: I was commissioned to produce a sound/audio work, to accompany the Right to Roam banner project. I collaborated with a musician and sound artist, who collated and edited the work I sent. Initially, I contacted people who were involved in land protest— be that through politics, history, writing, music, or art. I gathered a group of people willing to take part, and sent them chosen texts, poems, and slogans. My initial idea was to have prose and poetry that reflected romantic, pastoral themes, to contrast to the political nature of the banner. Then, in conversation, we decided there should be some more radical words involved. So, I decided to make two separate works: one poetic and romantic; the other reflecting protest in this context. Having previously worked with the actor, Maxine Peake, and knowing her interest in the Kinder Trespass (she was involved in the celebrations as an eight year old), I was delighted when she offered to contribute to this work.