ASHLEY'S SACK

Understanding the horror of slavery is impossible. But a simple cotton sack can bring us a closer. Historian Tiya Miles’ book traces the lives of three Black women through an embroidered family heirloom known as “Ashley’s sack”.

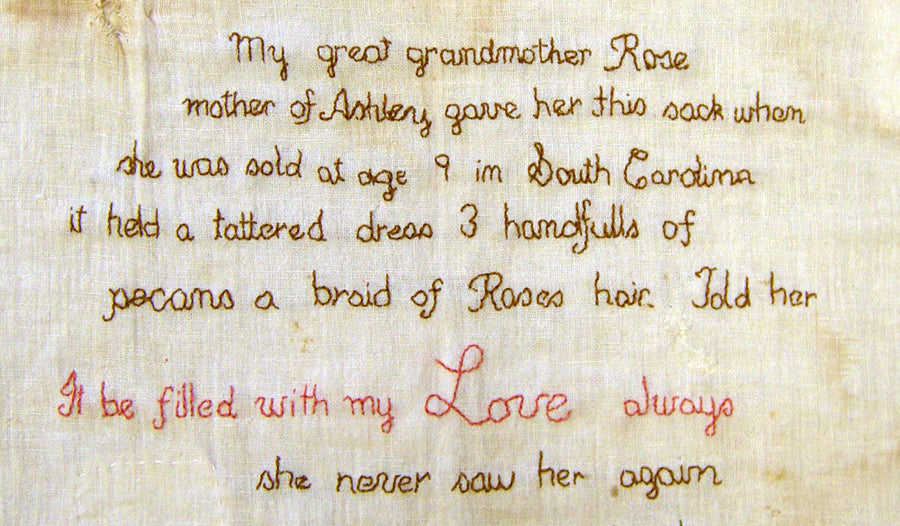

The cotton sack, much mended, is embroidered with a hundred-year-old stitched notation: “ ‘My great grandmother Rose/ mother of Ashley gave her this sack when/ she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina/ it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of/ pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her/ It be filled with my Love always/ She never saw her again/ Ashley is my grandmother’—Ruth Middleton/ 1921.”

This object, known as “Ashley’s Sack,” is the subject of historian Tiya Miles’ new book, All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. All That She Carried is a master class in the use of context in historical writing. Stymied by a lack of records, Miles thinks around the sack from every available angle: enslaved women’s relationships to their clothes, the meaning of hair in the 19th century, what we know about enslaved children’s reactions to separation, how Ashley might have gotten her name (an unusual one, for an enslaved girl), the natural history of pecan trees in the South. Through her interpretation, the humble things in the sack take on ever-greater meaning, its very survival seems magical, and Rose’s gift starts to feel momentous in scale.

Rebecca Onion spoke to Tiya Miles about the process of writing her book and the uniquely powerful object. Tiya wrote:

"The power of this object [Ashley's sack] seems to emanate from it, whether a person is seeing it from a distance, on the page of a book or on a screen, or up close and personal in a museum exhibit. And I think the power is anchored in the materiality of it, the fact that it’s a concrete and tangible item, and then the emotionality of what’s expressed on the surface of the sack, through the embroidered story. So the experience of engagement for the viewer or reader is a double or triple whammy—there are all these different modes of connection with the thing itself.

The way I tried to convey this in the book was, you take a few steps back from the sack to talk about that space of emotion, that experience of feeling the kinds of things that we do often want to sidestep in historical investigation. I think that to have avoided emotionality in the research and interpretation of the sack would have been to set aside an important aspect of the meaning of the sack, to the women who packed it and gifted it and carried it, and also potentially for us today.

This was somewhat of a struggle for me as a scholar, because so many of us are trained to try to adopt an objective stance in relationship to our sources. And though of course I have attempted to work within the accepted and proven methodological parameters of my discipline, I had to really make space for myself to relate to this object in a different way, and also to write about that mode of relating in the book—to be transparent about it, to expose it, and to encourage readers, people who have seen the sack in person or who will see an exhibit with it in the future, to be open to the feelings. That’s where so much of the power lies, so much of the usefulness for us today.

Image: Ashley's Sack. Courtesy Middleton Place Foundation. Cotton, thread, 75 x 40 cm. Created 1850s; embroidering added 1921. Discovered Nashville, Tennessee.

When I started the project, I hoped and expected I’d be able to identify the women who are named on the sack, to understand something more about their relationships, and to really trace them through time. And also to be able to trace more about the origins of the sack itself—to identify where it had been produced, and by whom. And with what specific materials.

I was very quickly disappointed to realize that records about all these things—the women, their relationship, their history, where they were from, the manufacture of the sack—were either nonexistent or had not been saved. And so what I thought was a project headed straight toward historical investigation turned into something else entirely. It turned into a deeply exploratory and experimental project. … I had to confront the paucity of sources and recognize that the book was going to be very different than what I had at first imagined, and recognize that this deficit could be a benefit for the project.

Harriet Jacobs, a formerly enslaved woman, told us in her writing that we could not know what slavery was. We just do not have that capacity. She said this to her white, free Northern women readers back in the 19th century—but we, too, due to our moment in time and place, can’t know.

And so we are in this place of not knowing, which is difficult for the scholar. But I think in the end, without this information, I was pushed to narrate the history of these women and their sack differently, and I hope that this will bring the readers a bit closer to the experience. These women had to stretch, bend, experiment, and innovate just to stay alive, to maintain their ties to one another, to their daughters, their sons; they had to innovate to tell their stories. And it has been an incredible gift and a learning experience for me to do something like the same in the research and writing of this book."

Read the full interview between Rebecca Onion and Tiya Miles at Slate.com.

We're delighted that author Tiya Miles will be taking part in the first Selvedge Literary Festival, a celebration of the varied literature forms that reveal and document the history and culture of cloth.

Book your tickets and find out more about the Selvedge Literary Festival here:

1 comment

I’m looking in as an outsider, but having read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s ‘Braiding Sweetgrass’, the pecans and braid seem to suggest a link to Native American culture