Dyeing for her art The Textile Art of Yto Barrada

Textile is having its moment in the world of Fine Art. The Barbican’s Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art is a case in point, but private Fine Art Galleries in the UK have been less inclined to share the wonder of textiles with their collectors. Pace Gallery has, however, embraced the work of Moroccan-American artist Yto Barrada with a new show, ‘Bite the Hand,’ a playful allusion to mordant—a dye fixative and the word for biting in French.

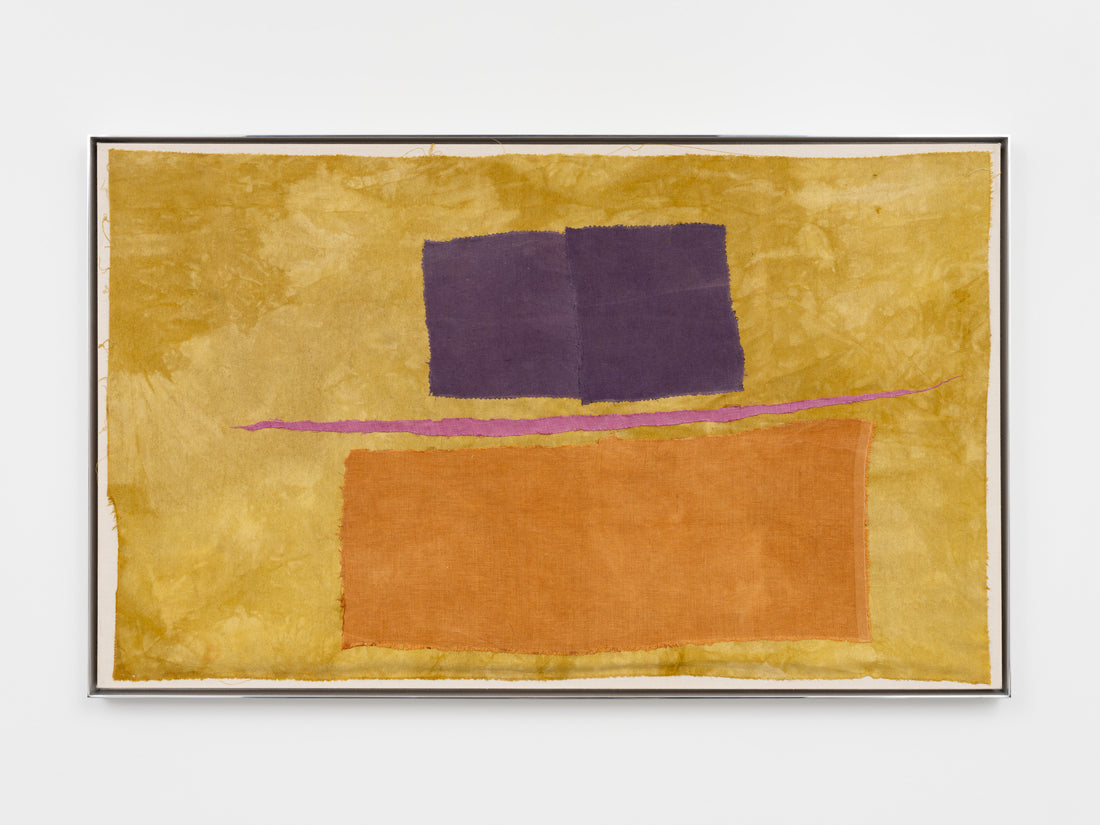

Image: Yto Barrada Untitled (Color Wheel I), 2024, Cotton and natural dyes, 31-1/2" × 31-1/2" × 2- 9/16" (80 cm × 80 cm × 6.5 cm), framed. Image above: Yto Barrada , Untitled (After Stella, Melilla V), 2019, cotton and natural dyes 80-5/16" × 137-13/16" (204 cm × 350 cm). © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery

Image: Yto Barrada Untitled (Color Wheel I), 2024, Cotton and natural dyes, 31-1/2" × 31-1/2" × 2- 9/16" (80 cm × 80 cm × 6.5 cm), framed. Image above: Yto Barrada , Untitled (After Stella, Melilla V), 2019, cotton and natural dyes 80-5/16" × 137-13/16" (204 cm × 350 cm). © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery

Barrada, based in New York and Tangier, works across media, using film, print, wood, and cloth, but is concerned with the physical and making. Her practice examines the decomposition and materiality of colour, which she uses to observe the tensions between colonial and capitalist systems, including time management and the forces of nature. She has a particular interest in textiles, as is made clear in this show. She dyes her cloth, mostly cotton, silk and velvet, stitching it into wall panels in various ways. These vary from almost Josef Albers-like works- collages of mostly off-centre geometric shapes, to pieces that look like exercises in quilting. The show includes a folding screen, colour samplers and sewing exercises.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (After Stella, Sidi Ifni IV), 2023, cotton, dye from plant extracts, 40-3/4" × 40-3/4" (103.5 cm × 103.5 cm), unframed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (After Stella, Sidi Ifni IV), 2023, cotton, dye from plant extracts, 40-3/4" × 40-3/4" (103.5 cm × 103.5 cm), unframed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery

However, Barrada’s specific interest is growing plants for dyeing, which she does in her garden estate, ‘The Mothership,’ near Tangier in Morocco. Set on a mountain west of Tangier, it commands a view of the Straits of Gibraltar and the southern tip of Spain. Her ‘How to Plan a Garden’ series in the exhibition is a drone-like viewpoint of her planting in this garden. Barrada learnt to dye in New York, but wanting to care for her family home in Tangier, she came up with the idea of growing her plants. “I have my varieties of indigo for blue, my madder root for reds, and plenty of wildflowers for yellows and greens. By digging in, you discover what is under your nose: leaves, roots, bark, lichens, and mushrooms. Everything was under my feet: I only needed to learn how to ‘read it,” she enthuses.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (Pu-P-O/Y), 2023, silk, linen and cotton with natural dyes, 24-7/16" × 39-3/4" × 1-15/16" (62.1 cm × 101 cm × 4.9 cm), framed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (Pu-P-O/Y), 2023, silk, linen and cotton with natural dyes, 24-7/16" × 39-3/4" × 1-15/16" (62.1 cm × 101 cm × 4.9 cm), framed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Barrada enjoys gardening, finding it “almost spiritual. You feel very small in a garden because the more you know, the less you know.” Her planting is ecological but also a political gesture, rejecting the monoculture that has been developed in Morocco to provide Europe with hot-housed strawberries and bananas. Indeed, all her work has a political element. She was one of the initiators of withdrawing artworks from Unravel at the Barbican.

Barrada has created the Dye House at ‘The Mothership’ with the help of the ArtAngel International Fund and patrons such as her gallery Pace. She hosts workshops, conducting experiments using plants and insects to produce the dyes for her textile pieces. With a climate control system, she will be able to store and test how produce differs each year because of climate variations and during storage. “There’s a whole library of colours to build. Residents coming in will contribute to the colour library by making colours and leaving the recipes for the next ones.”

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (How to Plan a Garden II), 2024 noi silk, 35-1/4" × 29-1/8" × 1- 1/2" (89.5 cm × 74 cm × 3.8 cm), framed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (How to Plan a Garden II), 2024 noi silk, 35-1/4" × 29-1/8" × 1- 1/2" (89.5 cm × 74 cm × 3.8 cm), framed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Her works use homegrown indigo, madder, and eucalyptus to create blue, pink, and grey, alluding to the history of Botany in Morocco. These works reference women who were historically described and treated as witches because of their knowledge of plants. Barrada uses plants and dyes to imbue her work with such political and ancestral narratives, seeking to investigate strategies for survival, resistance, and rebellion.

‘The Mothership’ is partly named after her mother and grandmother and the community of women she has worked with. She created what she calls an ‘eco-feminist’ and ‘afro-futuristic’ environment. The latter is a speculative fiction genre through which Black thinkers, practitioners, and writers imagine a new and Afrocentric future. The intention is that artists can come to develop their practice, yet she is also keen to harness the knowledge of displaced women who have come down from the mountains to find jobs in Tangier.

Her hopes for the future of ‘The Mothership’ are nothing if not ambitious. “I want it to be sustainable; I want it to function when I’m not there. I’d like it to be ambitious in the sense that I think there’s an urgency in the work we do with colours. There are so many applications.” She is keen to encourage the use of natural dyes from food waste, such as onion, pomegranate and avocado skins or the use of naturally available materials like the shed bark of eucalyptus. “I’d love to work with scientists, universities, biochemists. The whole challenges in bio design. I’m very interested in colours from mushrooms and lichens.” For Barrada, the garden is a research project in itself.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (How to Plan a Garden I), 2024 noi silk, 26" × 26-1/2" (66 cm × 67.3 cm). © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (How to Plan a Garden I), 2024 noi silk, 26" × 26-1/2" (66 cm × 67.3 cm). © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

The investigation of colour is fundamental to her practice; she uses colour as a measure of time. “I’m interested in decay and in the materiality of colour.” In the exhibition, her film ‘A Day is Not a Day’ shows how she has set up large-scale experiments to see how colours fade and weather over time. She uses this to look at the effects of climate change, one of her many interests. Postcolonial ideas inform her work, and she looks at immigration, tensions around borders, landscape, and tourism. This socio-political element is hardly surprising, given her background. Born in Paris in 1971, she grew up in Morocco before studying history and political science at the Sorbonne, followed by photography in New York. She helped with the establishment of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut (late 1990s) and co-founded Tangier’s Cinémathèque in 2006, North Africa’s first combined arthouse cinema and film archive. Her work has been exhibited around the globe, and among the many prizes she has received is the Queen Sonja Print Award (Norway) 2022.

Barrada’s practice glorifies the random. She uses offcuts and discarded sewing exercises to create new work: “I have all my boxes of colours. I don’t pick pieces; I don’t have a plan. It’s not like a quilt or drawing. I make a lot of colours, and when all the colours are together, I just paste everything on the walls. And it’s very organic. I think that going further, I’d love to have an automatic system of production. I could have a machine that gave me instructions, and I can do the colours and grids.” She recently found that Emily Noyes Vanderpoel’s treatise Colour Problems (1903), which contains gridded colour analysis that prefigures much abstract art, could be made into a machine. Vanderpoel would turn objects “into a minimalist grid of just a column. And I have found two women at MIT who make the software where you put any image in, and you get a grid of colour, to produce automatic poetry.”

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (G-P-Gr/Y), 2023, silk, linen and cotton with natural dyes 19-7/8" × 14-15/16" × 1- 15/16" (50.5 cm × 37.9 cm × 4.9 cm), framed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Image: Yto Barrada, Untitled (G-P-Gr/Y), 2023, silk, linen and cotton with natural dyes 19-7/8" × 14-15/16" × 1- 15/16" (50.5 cm × 37.9 cm × 4.9 cm), framed. © Yto Barrada, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Many of the pieces in this show are quite low-key. The collages in silk, velvet and cotton are the most intriguing. For many textile aficionados, her use of cloth and her pattern-making will seem relatively simple and basic but become more intriguing with an understanding of the ideas behind it. Sadly, the show does not give much information on this or ‘The Mothership,’ but it is an introduction to Yto Barrada and her concerns.

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art is on show at the Art Gallery, Barbican until

Barrada, based in New York and Tangier, works across media, using film, print, wood, and cloth, but is concerned with the physical and making. Her practice examines the decomposition and materiality of colour, which she uses to observe the tensions between colonial and capitalist systems, including time management and the forces of nature. She has a particular interest in textiles, as is made clear in this show. She dyes her cloth, mostly cotton, silk and velvet, stitching it into wall panels in various ways. These vary from almost Josef Albers-like works- collages of mostly off-centre geometric shapes, to pieces that look like exercises in quilting. The show includes a folding screen, colour samplers and sewing exercises.

However, Barrada’s specific interest is growing plants for dyeing, which she does in her garden estate, ‘The Mothership,’ near Tangier in Morocco. Set on a mountain west of Tangier, it commands a view of the Straits of Gibraltar and the southern tip of Spain. Her ‘How to Plan a Garden’ series in the exhibition is a drone-like viewpoint of her planting in this garden. Barrada learnt to dye in New York, but wanting to care for her family home in Tangier, she came up with the idea of growing her plants. “I have my varieties of indigo for blue, my madder root for reds, and plenty of wildflowers for yellows and greens. By digging in, you discover what is under your nose: leaves, roots, bark, lichens, and mushrooms. Everything was under my feet: I only needed to learn how to ‘read it,” she enthuses.

Barrada enjoys gardening, finding it “almost spiritual. You feel very small in a garden because the more you know, the less you know.” Her planting is ecological but also a political gesture, rejecting the monoculture that has been developed in Morocco to provide Europe with hot-housed strawberries and bananas. Indeed, all her work has a political element. She was one of the initiators of withdrawing artworks from Unravel at the Barbican.

Barrada has created the Dye House at ‘The Mothership’ with the help of the ArtAngel International Fund and patrons such as her gallery Pace. She hosts workshops, conducting experiments using plants and insects to produce the dyes for her textile pieces. With a climate control system, she will be able to store and test how produce differs each year because of climate variations and during storage. “There’s a whole library of colours to build. Residents coming in will contribute to the colour library by making colours and leaving the recipes for the next ones.”

Her works use homegrown indigo, madder, and eucalyptus to create blue, pink, and grey, alluding to the history of Botany in Morocco. These works reference women who were historically described and treated as witches because of their knowledge of plants. Barrada uses plants and dyes to imbue her work with such political and ancestral narratives, seeking to investigate strategies for survival, resistance, and rebellion.

‘The Mothership’ is partly named after her mother and grandmother and the community of women she has worked with. She created what she calls an ‘eco-feminist’ and ‘afro-futuristic’ environment. The latter is a speculative fiction genre through which Black thinkers, practitioners, and writers imagine a new and Afrocentric future. The intention is that artists can come to develop their practice, yet she is also keen to harness the knowledge of displaced women who have come down from the mountains to find jobs in Tangier.

Her hopes for the future of ‘The Mothership’ are nothing if not ambitious. “I want it to be sustainable; I want it to function when I’m not there. I’d like it to be ambitious in the sense that I think there’s an urgency in the work we do with colours. There are so many applications.” She is keen to encourage the use of natural dyes from food waste, such as onion, pomegranate and avocado skins or the use of naturally available materials like the shed bark of eucalyptus. “I’d love to work with scientists, universities, biochemists. The whole challenges in bio design. I’m very interested in colours from mushrooms and lichens.” For Barrada, the garden is a research project in itself.

The investigation of colour is fundamental to her practice; she uses colour as a measure of time. “I’m interested in decay and in the materiality of colour.” In the exhibition, her film ‘A Day is Not a Day’ shows how she has set up large-scale experiments to see how colours fade and weather over time. She uses this to look at the effects of climate change, one of her many interests. Postcolonial ideas inform her work, and she looks at immigration, tensions around borders, landscape, and tourism. This socio-political element is hardly surprising, given her background. Born in Paris in 1971, she grew up in Morocco before studying history and political science at the Sorbonne, followed by photography in New York. She helped with the establishment of the Arab Image Foundation, Beirut (late 1990s) and co-founded Tangier’s Cinémathèque in 2006, North Africa’s first combined arthouse cinema and film archive. Her work has been exhibited around the globe, and among the many prizes she has received is the Queen Sonja Print Award (Norway) 2022.

Barrada’s practice glorifies the random. She uses offcuts and discarded sewing exercises to create new work: “I have all my boxes of colours. I don’t pick pieces; I don’t have a plan. It’s not like a quilt or drawing. I make a lot of colours, and when all the colours are together, I just paste everything on the walls. And it’s very organic. I think that going further, I’d love to have an automatic system of production. I could have a machine that gave me instructions, and I can do the colours and grids.” She recently found that Emily Noyes Vanderpoel’s treatise Colour Problems (1903), which contains gridded colour analysis that prefigures much abstract art, could be made into a machine. Vanderpoel would turn objects “into a minimalist grid of just a column. And I have found two women at MIT who make the software where you put any image in, and you get a grid of colour, to produce automatic poetry.”

Many of the pieces in this show are quite low-key. The collages in silk, velvet and cotton are the most intriguing. For many textile aficionados, her use of cloth and her pattern-making will seem relatively simple and basic but become more intriguing with an understanding of the ideas behind it. Sadly, the show does not give much information on this or ‘The Mothership,’ but it is an introduction to Yto Barrada and her concerns.

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art is on show at the Art Gallery, Barbican until