Faith Ringgold

On the opening of the African American Artists Fath Ringgold first show in the UK, at the Serpentine Gallery, London, we look back at an article on her work from issue 04 written by Dr. Catherine Harper

Have Faith

Colourful and carefully constructed, these quilts communicate eloquently

Faith Ringgold’s website – www.faithringgold.com – states “if you are an artist, writer, teacher, or a kid of any age who loves art and stories you may just be in the right place”. The generosity of this welcome sets the tone for her site and for her practice.

Ringgold, originally a painter, makes painted story quilts, mixtures of painted and quilted fabrics, pictorial in content, frank in form and accessible in style. Apparently simple, they tell stories of lives lived as African-American women and men in a culture constructed from their blood, sweat and tears, and often neglectful of their needs and aspirations. And, by sewing soft pictures, with narrative imagery and colourful motifs, Faith Ringgold persists in making a strong and memorable impact.

Faith Ringgold was born in 1930 and raised in New York, experiencing the double politicisation of a black urban woman at the genesis of feminism and the birth of 'black power'. As a young female artist in the early 1960s, Ringgold felt the full forceful affect of the Civil Rights movement and the first wave of US feminist activism. These turbulent and energising influences were reflected at that early point in her artistic career in her adoption of bold, graphic images in dark colours and her desire to represent black faces, cultures and histories in a visual culture almost exclusively drawn from European white male tradition.

I became aware of Ringgold in 1987 when I was raising my own singular consciousness in Belfast. A marginalised fledgling 'solo-feminist' – by which I mean 'one who didn't know another', I was drawn to the work of certain African-American feminist practitioners whose work then seemed to be 'on the edge of the edge' - of politics, of feminism, of material practice, of visual culture. Betty Saar, Harmony Hammond, Barbara Chase-Riboud and Faith Ringgold provided me with a context so completely different from my own that it went full circle to allow me both to empathise and be inspired.

The 1970s saw the development of new forms of feminist collaborative visual culture, exemplified perhaps by Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party which incidentally honours only one black woman – Sojourner Truth – amongst 39 but nevertheless challenges the privilege of stretched canvas and 'high art' materials. Ringgold made her transfer from painting practice to quilting when she began to work with her mother to sew fabric borders around her paintings. Eventually, echoing the traditions and conventions of collaboratively formed North American quilts, they produced one quilt together - Echoes of Harlem – pulling together the portraits of 30 Harlem neighbours in a work of compelling simplicity, inclusiveness, and readability. Here we have a populace positioned around the edges and in the centre of what is unmistakeably a quilt format. Faces are the good, bad and ugly of friends, family and extended locale. They turn towards and turn away from each other, patterned to create dialogues, relationships and sub-groupings, as is a neighbourhood. There is a sense that if we turn away and look again, the faces will have changed.

Ringgold's first solo story quilt, made after her mother's death, narrates in imagery the story of a successful black American businesswoman. Who's Afraid of Aunt Jemima? combines acrylic painting on canvas with quilted fabric and the text of a hand-written story. Ringgold counters the oppression, stereotyping and deprivation encountered in her neighbourhood with an engagingly powerful optimism and implicit encouragement to 'take flight' and follow dreams.

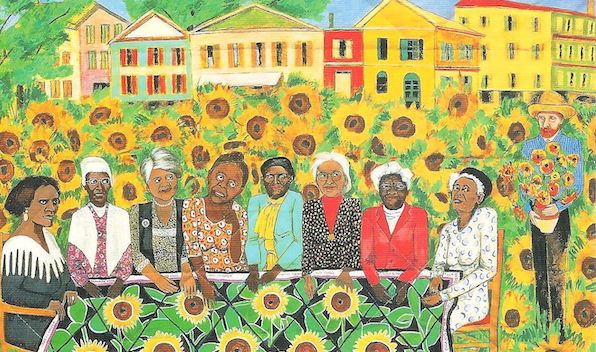

Bold luminous colours, usage of 'folk' style, without perspective, with two-dimensional patterning and no shading mask the complexity of Ringgold's meanings. Issues of race, gender, art history and contemporary culture have been constant themes. Ringgold has examined the fetishisation of black women in the visual imageries of European history, the exoticising of so-called 'primitive' cultures of Africa and the relation of the black 'other' in juxtaposition to white normative privilege. In The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles ,1991, Ringgold quilts a group of African-American women showing off a sunflower quilt, in a field of sunflowers, with Van Gogh in the background, holding a vase of sunflowers. There is a witty story-within-a-story feeling to this work, a delightful evocation of Arles-esque colour and passion, a kindly repositioning of a key male painter of history, but a repositioning that places him where he was anyway – on the margin.

If Ringgold's mother showed her how to sew, her great-great-grandmother showed her how to piece, patch and pad fabrics in the time-honoured fashion of making quilts or comforters. But more than the textile history, the woman who taught Ringgold to quilt taught her – from lived experience – about the slave tradition of US American culture. That woman's early quilts were made for her white slave-masters, a process of making and taking much written and spoken of in the histories of slave culture. Slave quilts – like those made by Harriet Powers – added another dimension to the usual functions of comfort, warmth, decoration and narration that quilting normally engenders. There has been much speculation about the signals, non-textual messages and coded information contained in slave quilts. Jacqueline Tobin's controversial publication Hidden in Plain View: The Secret Story of Quilts about the “Underground Railroad” recounts a story of quilt imagery being used as a secret code that assisted escaped US slaves to find their way northwards towards freedom, while the much publicised Quilts of Gee's Bend, a collection of 20th century quilts made by a Southern Alabama community, are made in and by women whose grandmothers were the enslaved 'goods' of a certain John Gee.

With these legacies in mind, Ringgold chose to join the diverse company of women artists in the 1970s who were making art objects in the traditional media and materials of 'women's work' – textiles, sewn fabric, weaving, quilting, embroidery – but refusing 'craft' association in favour of self-elected 'new high art' status. And her success at straddling the agendas of that movement, a feminist movement that arguably erased its internal differences of ethnicity, class and sexuality to present a highly problematic female essentialism, is testimony to a clarity of vision obvious in her singularly focussed practice.

In The Men: Mask Face Quilt, 1986, Ringgold places mask-like African-American male faces in a grid-system quilt pattern. Her work, its title and subsequent writing about this piece references both the 'African-ness' of the mask reference and the defensiveness of inscrutable faces giving little away. Where prejudice based on skin colour is experienced, and the colour of one's face cannot be hidden, the face becomes both a proud revelation of race and a site of secrecy, the last barrier of the soul. This work speaks about the face as mask: a front, a presentation, a cover… Much as a quilt is decorative, comforting, functional and at the same time saturated with meaning and resonance, these faces are comfortably pictorial while simultaneously being hugely loaded with cultural significance and personal narrative meaning. That is the essence of Faith Ringgold's practice. •••

Words by Dr. Catherine Harper

From 6 Jun 2019 to 8 Sep 2019 www.serpentinegalleries.org