PANTO!

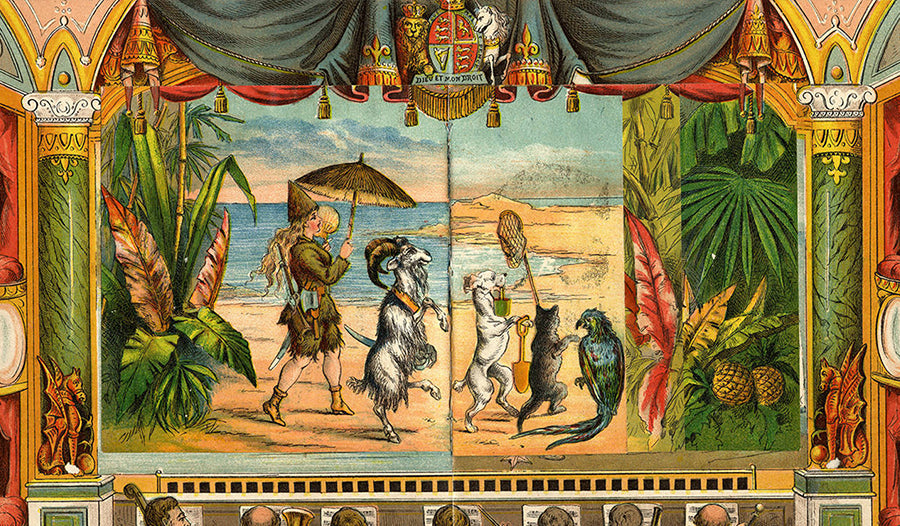

Image: Printed programme for Robinson Crusoe at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, December 1881, England. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Image: Printed programme for Robinson Crusoe at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, December 1881, England. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As Cinderella magically appears in a stunning ballgown and sparkling tiara, almost instantly changed from the kitchen maid dressed in rags, few people in the audience today realise they are witnessing one of the last remnants of a great Victorian pantomime favourite – the transformation scene. With its host of chorus girls dressed in gloriously extravagant costumes, laboriously sewn by hand with sequins and tinsel to glitter in gaslight, this was the pantomime highlight that the wealthiest London theatres executed with increasing fervour, and even the smallest theatres strove to emulate.

Today's audiences expect colourful, extravagant costumes in pantomime, but many of its traditional characters and their distinctive costumes have been relegated to the annals of theatre history. Their names may be familiar, but the evolution of their dress and its place in pantomime history is less well known.

Image: A Christmas Transformation, illustration from The Publisher magazine, 1881, England. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Image: A Christmas Transformation, illustration from The Publisher magazine, 1881, England. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Pantomime was invented on the London stage over 300 years ago, when Harlequin was its star. He was first seen in 17th century England as Arlecchino, a leading comic character with visiting Italian 'Commedia dell'arte' companies. Early woodcuts and engravings depict him in a long, belted jacket and trousers featuring multicoloured patches signifying his humble origins, and carrying his magic sword or bat. He wore a full black mask, and a soft cap decorated with the tail of a rabbit, hare or fox, possibly a reference to the peasants of his native Bergamo, who similarly decorated their hats. When Harlequin appeared on the London stage in 1717 at Lincoln's Inn Fields played by the actor-manager John Rich in Harlequin Sorcerer, he was an immediate hit as a masked, acrobatic, dancing, non-speaking character, wearing short jacket, belted and buttoned, and fitting trousers featuring a criss-cross design.

This marked the transition between the traditional Italian dress of 'shreds and patches' and the elegant, sequinned Harlequin of the Regency stage as introduced at Drury Lane Theatre in 1800 for the pantomime Harlequin Amulet by the dancing master James Byrne. His celebrated Harlequin wore a fitted one-piece suit covered with hundreds of triangles of cloth and thousands of spangles. He wore a small Venetian eye mask, and introduced significance to the colours in his costume, such as yellow for jealousy and black for invisibility, to which he pointed with his bat.

By this date pantomimes were two-part entertainments, the second part a comic chase or Harlequinade featuring the love affair of Harlequin and Columbine thwarted by Columbine's protective parent Pantaloon, with with the farcical interference of clown. Columbine, originally a waiting-maid with the Commedia, wore the short skirts of a dancer, fetchingly displaying a well-turned ankle, while her disciplinarian father wore a version of the Italian convention of a short jacket, and knee-length breeches, dispensing with the long cloak, little Greek cap and hook-nosed mask.

Pantomime audiences were used to seeing Clown as a ruddy-cheeked country bumpkin, a ragged servant or peasant, but Dibdin introduced: 'dresses that were more extravagant than it had been customary for such characters to wear', and featured two such brightly dressed clowns in his pantomime - Guzzle the drinking clown played by the new clown Grimaldi, and Gobble the Eating Clown played by Sadler’s Wells' previous favourite, Jean-Baptiste Dubois. Grimaldi's voluminous breeches were perfect for concealing the stolen sausages, legs of mutton, and even live geese that packed their capacious pockets, and the public was entranced by the newly-styled clown with his fantastic make-up and wigs, especially when he made the part his own in the 1806 Covent Garden pantomime Harlequin Mother Goose, or the Golden Egg. The mid-century clown Richard Flexmore made the costume tight-fitting again to suit his more balletic interpretation of the character, but as the century progressed and the nature of pantomime changed, the emphasis shifted from both Harlequin and Clown. The Harlequinade became shorter, stories from fairytales were introduced, and more familiar pantomimes and characters began to emerge, including the Principal Boy and the Dame.

The costume of the Principal Boy owes its existence to the growing popularity in the early 19th century of the leading young man's role being played by a woman dressed in breeches and tights, revealing a shapely leg. The first such pantomime 'breeches role' appeared in the 1815 pantomime Harlequin and Fortunato, when a girl in man's dress was transformed into Columbine, and four years later Eliza Povey played Jack in the 1819 Drury Lane pantomime Jack and the Bean Stalk, or, Harlequin and the Ogre. In the 1830s the actress manager Lucy Eliza Vestris became famous for revealing her legs in the costumes she wore in boy parts in operatic burlesques and extravaganzas, and by the mid 19th century several actresses were dispensing with breeches entirely. Lydia Thompson's daring costume for her title role in the 1876 'Christmas burlesque' Robinson Crusoe – at a time when women’s dress covered the ankles – was rapturously described in a contemporary account: ‘Her wonderful white dress was composed of layer upon layer of fringe of the angora goat, sewn upon a body and short skirt of white silk. A high-peaked cap of the same material enlivened by a stiff feather of the brightest scarlet of the flamingo's wing, white satin boots, and long gloves, belt and chatelaine of polished silver, white Chinese parasol, a tame parrot perched on the forefinger of her left hand. Thus attired she made quite a striking appearance of prettiness.’

As glamorous costumes that accentuated the hour-glass figures of the Principal Boy became an essential ingredient of late Victorian and Edwardian pantomime, so the popularity of men dressed as the Dame correspondingly increased. Samuel Simmons donned skirts for his role as Mother Goose as early as 1806 and Grimaldi himself reduced audiences to fits of laughter by disguising himself in female clothes. But the convention of the comic Dame was not universally accepted in pantomime until the 1860s. By the 1880s, when Dan Leno made the part his own, he achieved the comic effect by simply wearing an 'old maid's' outfit of bonnet, shawls, petticoats and skirt, an unprepossessing wig and simple make-up. Many celebrated 20th century Dames such as Cyril Fletcher, Arthur Askey and Les Dawson preferred Leno's incongruity of costume, retaining an essentially masculine appearance while skipping in skirts.

Image: Left to right, Miss Rosie St. George as Boy Blue in Little Bo Peep, Miss Maud Boyd as Robin Hood, Ada Blanche as Robinson Crusoe, The Sketch Magazine, 27 December 1893, England. Museum no. 131655. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In contrast, Danny La Rue developed the Dame as a gloriously feminine creation, using his own costume designers to create splendidly sophisticated yet comic costumes, and fabulously expensive feathered and sequinned gowns, complete with matching wigs and accessories. Although the popularity of the female Principal Boy has waned today, increasingly inventive and comic Dame costumes are still an essential ingredient of contemporary pantomime, featuring as many as fifteen different and increasingly outlandish outfits in each show. As John Inman once remarked: ‘An Ugly Sister isn't much more than a coat-hanger. All you do is wander in, say a couple of lines, and wander off to change your clothes.’ As the Ugly Sister in Cinderella he was in the bath when the Prince called, so made his entrance in a bathroom creation of washbasin wig complete with taps and chain, loo mats on his shoulders, a bath mat skirt and a tasselled towel.

Image: Left to right, Dan Leno as Widow Twankey in Aladdin at the Drury Lane Theatre, 1896, England. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Samuel Simmons as Mother Goose in Mother Goose, or the Golden Egg, Covent Garden Theatre, 1806. Published by S. De Wilde, 1807, Harry Beard Collection

Nowadays Lady Gaga-inspired costumes are all the rage in the competitive world of Damedom; as the specialist Dame Nigel Ellacott notes: ‘We need to be funny before we open our mouths. We're striving for the show-stopper.’ With costumes costing £1,000 or more, no expense is spared on fantastic and bizarre creations for the Dame today – perhaps the most enduring comic creation in pantomime that would even have made Rich laugh, Grimaldi guffaw, and Lydia Thompson slap her buxom thigh.

--

He's Behind You! Pantomime Costumes of the Past and Present, written by Catherine Haill, from Issue 37 Dress Circle.