SOIL TO SOIL

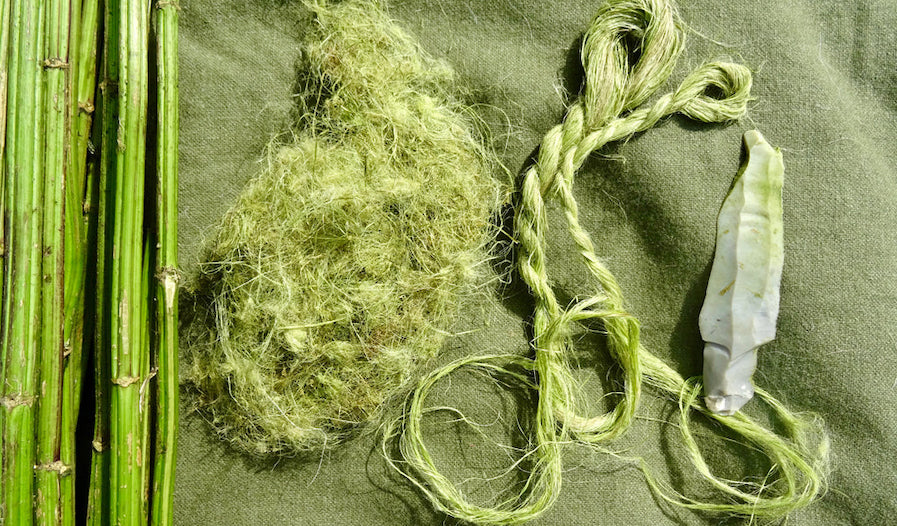

Image courtesy of Allan Browns of Hedgerow Couture

Text: Primrose Russell, co-founder of UK-based compostable underwear brand, Bedstraw + Madder, which won the Drapers Sustainable Fashion Award for 2022, talks to SELVEDGE about the beauty of ‘soil to soil’ clothing.

There is a wave happening— a colourful one, infiltrating our wardrobes and our interiors. Since lockdown, our connection to the natural world has been heightened, along with our appreciation and understanding of its healing virtues. An interest in natural colour has been sparked.

Lady’s Bedstraw (Galium verum) is a plant that traditionally grew in the chalky green and pleasant land of England. Historically important for dyeing our homegrown fabrics of hemp and flax, it is now largely unknown, and largely missing from our countryside. It furnishes a yellow dye from its stem when simmered, and a coffee substitute from its seeds when toasted.

Image: Whortleberries. Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder.

Image: Whortleberries. Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder.

On our British moors grow Whortleberries (Vaccinium scoparium), whose purples and blues were used to dye the uniforms of the navy during the First World War. Since the arrival of synthetic purple, invented by Henry Perkin in 1982, fabric dyeing has gone from beautiful, never clashing shades derived from plants, minerals, and animals, to crude oil-based colour. This new chemistry was created to bring efficiency, longevity, and economic benefit but, in exchange, it has left poisoned waterways, diseased communities, and contributes to 20% of global water pollution, annually.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

As the detrimental effect of human activity on the natural world becomes ever more alarming, and we seek to repair the damage, now seems the perfect time to return to clean, natural colour, to seek a healthier solution for people and planet alike.

Plant dyeing is alchemy; a wisdom passed down through generations. It represents a revival of the ancient, of the land, of biodiversity, and of crafts and techniques that have been around for centuries. Returning to this art, and eliminating chemicals and bleaches from our colours, makes logical sense. To eliminate chemicals from our fabrics creates healthy, living cloth. In order to do this, you need to start with the seed. You need to know every part of the journey your fabric has been on, and ensure it hasn’t been contaminated along the way.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

Jump to the sun-baked fields of Erode, India, where a new fashion system is being cultivated, rooted in ancient agricultural practices. Here, they are growing the new generation of cotton, the ‘Queen of Sheba’— organic, regenerative cotton. Pesticide and fertiliser free, each boll sequesters carbon from the atmosphere, reviving the life of our soil, and securing biodiversity for future generations to enjoy.

Pioneered by visionaries like Nishanth Chopra of Oshadi Collective, and Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of Raddis Cotton, regenerative organic is the new standard for cotton production. Utilising no till, and preserving animal husbandry, and cover cropping methods to repair and protect our soil, this is not just about environmental impact. Women undertake 80% of the work done in the fields. The regenerative approach is a holistic approach, focusing on empowering women, and regenerating communities as well as land. A radically transparent supply chain ensures fabric is spun, woven, and naturally dyed in the villages neighbouring the farms where it is grown. This ensures fair and sustainable production.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

Cotton is not naturally pearly white, as the chemical promoters might lead you to believe. Living cotton has a warm, ecru tone that flatters the paler tones of our skin. When you are dyeing with living colour, it is a joy to amplify those benefits by using a living fabric.

Indigo is perhaps one of the more familiar natural plant dyes. Its blue, antibacterial qualities were made famous by the Samurai warriors of Japan, who wore it beneath their armour, to prevent infection should they get wounded. The plant it is derived from is often used as a cover crop, after cotton has been planted. Being a legume, it fixes nitrogen into the soil, encouraging beneficial bacteria to flourish and fertilising the soil for its next planting. Marigold, another natural dye used for golden yellows, protects against pests when planted near a crop. Both represent the beautiful, symbiotic, and circular relationship between dye stuff and fabric, developed over millennia.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder. Photo: Aneel Kumar Ambavaram of GVK Society partnered with Raddis Cotton and Ashish Chandra.

When it comes to converting plants to pigment, the transformation carries the same magic. In southern India, the chemical-free process that transforms the Tacoma flower (Amatilla bignonia) into a lemony yellow is as follows:

The handpicked flowers are dried in both sun and moonlight, over three successive days. Then they are soaked in rainwater, and ground thoroughly to extract the colour. During dyeing, milk, plantain sap, and vegetables oils are added to achieve particular finishes on the dyed material.

Tacoma, like most plants, shares its unique benefits with the wearer. The plant possesses powerful antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties, due to its naturally high flavonoid content.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder.

Image: Courtesy of Bedstraw + Madder.

Each year, nature goes through a cycle of birth, growth, and decay, paving the way for new life. In order to be in harmony with nature, shouldn’t our clothing mirror this? The next generation of clothing is becoming known as ‘soil to soil,’ promoting a fully circular system that supports soil health, eliminates landfill, and celebrates natural colour in all its glory.

Here’s to a brighter future for our wardrobes, naturally.