Learn About Chinese Mud Silk History, Process & Design

Few textile processes in the world are so involved with every nuance of the climate as mud silk, a textile that follows a 2500 year tradition in Southeast China. Starting with silk, a biodegradable fibre, and using natural plant dyes, river mud, space, sunshine and the work of many people, mud silk can be called a one hundred percent ecological textile. Originating in Guangdong Province of China and dating back to the Ming Dynasty in the fifth century, this tradition has been kept alive within the region where a subtropical river delta carries an iron-rich mud that binds to the silk. Commonly known as Tea Silk, Lacquered Silk, Canton Silk, or Mud Cloth, Gambiered Silk has long been a traditional fabric used by the Hakka people. Its cultural significance was recognized in 2009 by the addition of the technique of dyeing xiang yun sha in Shun De to UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China. Gummed silk also extends beyond China, as it can be made wherever there is a tannin-rich river delta, intense sunshine and base colourants such as gambier (uncaria gambir), ju-liang root, or indigo. Iron is the fourth most abundant element in the earth's crust and leaches into freshwater rivers, lakes and ponds from soil and weathered rocks. The Mekong River, flows from China, along the Laos-Myanmar and LaosThailand borders, then across Cambodia. It becomes a rich delta when it reaches southern Cambodia and Vietnam, and provides the appropriate conditions, as does Thailand’s Chao Phraya River.

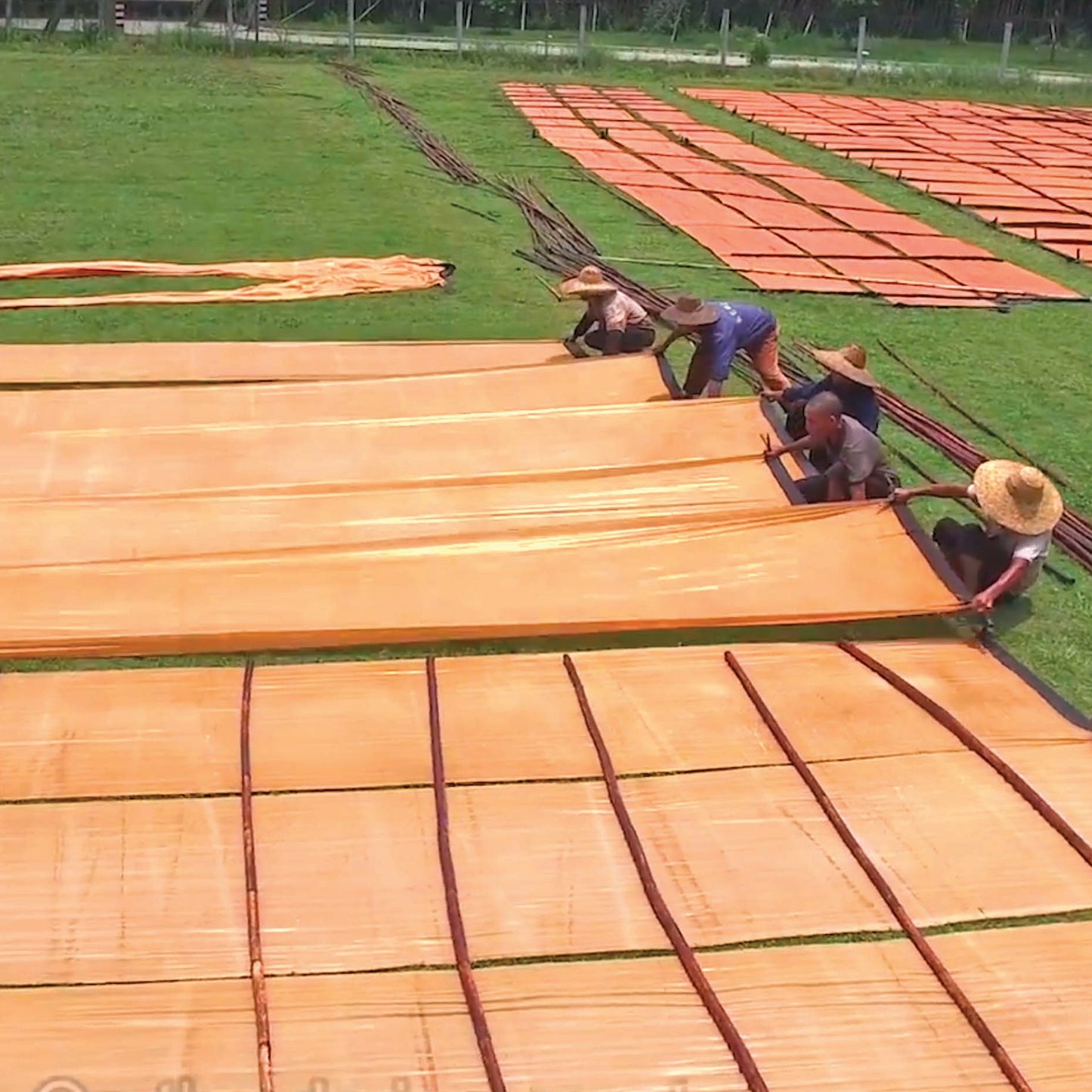

Physically the fabric has contrasting surfaces on each side; a glossy black face and a matte orange-brown reverse achieved using Yam-Dioscorea cirrhosa from Guandong, a medicinal tuber known for its antibacterial and antivirual properties which is an advantage of wearing this fabric for people who have sensitive skin. The black side, has a thin, dark, resin-like film on its surface which has water resistant properties, is durable and easy to care for. This, combined with its crisp, cool handle that gets softer with time, makes it a perfect choice for warm weather. The seasonal and complicated manual process starts with drying the yams followed by grinding and simmering them in a large clay basin until the water turn orange and the fabric absorbs the colour. This can be a lengthy process as it must be repeated many times depending on the depth of colour desired. Then the fabric is laid down to dry before it receives the layer of mud from the Pearl River. This gives the fabric a laquered texture that is formed with a thin layer of anthracite coal. It is important to note that although the technique is referred to as mud-dyeing, the mud is not the actual dye but rather a mordant - it is the tannin that is the dye. The initial tannin-dyeing stage is a hot process, but the subsequent mordanting in mud is cold. The production process to create mud silk is labour intensive and season specific and only occurs between March and November in Canton. Climate change has had a direct impact on this cultural practice for two reasons: changes in the iron content of the river due to pollution and changes in the seasons making it difficult for artisans to plan and respond to weather conditions. Marcella Echavarria www.noir-handmade.com

Marcella Echavarria is a designer and cultural entrepreneur who has dedicated her career to the study of textiles, craftsmanship, tradition and sustainability. She has worked with artisan communities across the globe, from Tibet to San Pedro Cajonos in a quest to preserve and document ancestral techniques as global heritage. The Noir collection, is a very personal project that truly embodies slow fashion, sustainability and a millenary textile tradition from China. The pieces in this collection were created to honor the fabric and a process that carries 2500 years of wisdom and skill of this extraordinary dying technique. Each garment is unique in that the patina created from mud dyes is like wearing the earth, the sky and the soul of the people who have dedicated their lives to texture and textile as livelihood.

Share